80 years ago: The Opening of Heathrow airport

On a bright, dry, frosty morning, on a windswept expanse of concrete, a man in homburg hat, made a speech in front of a Lancastrian Starlight airliner. He was Lord Winster, the Minister for Civil Aviation, and he was there, on 1 January 1946, to mark the inaugural flight from the £20million new airport that was being built in West London. Lord Winster told the dignitaries that Heath Row would be the future civil airport of London and it already had the finest runway in the world, “This flight is the first step towards the establishment of swift and regular British air services to South America. Air Vice-Marshal Donald Bennett and all those flying with him today are truly ambassadors representing the spirit and determination of Britain to play the same leading part in the air as it always has at sea.”[1] The aeroplane, piloted by the Air Vice-Marshal had a crew of six, including Mary Sylvia Guthrie, 24-year-old ex-pilot of the British Air Transport Auxiliary, as the first air hostess.[2] It was flying via Lisbon, Bathurst, Natal (Brazil), Rio de Janerio and Monte Video. The aircraft took off on the 3000 yard runway, but only needed 1000 yards before it was airborne. It was also the day that the airport, built on land requisition by the Air Ministry for wartime use, was officially handed over to the Ministry of Civil Aviation. It had never been used by the R.A.F. although the runways had been built in the triangular pattern favoured by the R.A.F. It was soon pointed out by Airline officials that 100-ton airliners would not be able to use the airport with this runway configuration if the wind was north or south. The current arrangement would only be suitable for small aircraft which can land in a cross-wind.[3]

[1] Halifax Evening Courier - Tuesday 01 January 1946

[2] Illustrated London News - Saturday 12 January 1946

[3] Daily Express - Wednesday 02 January 1946

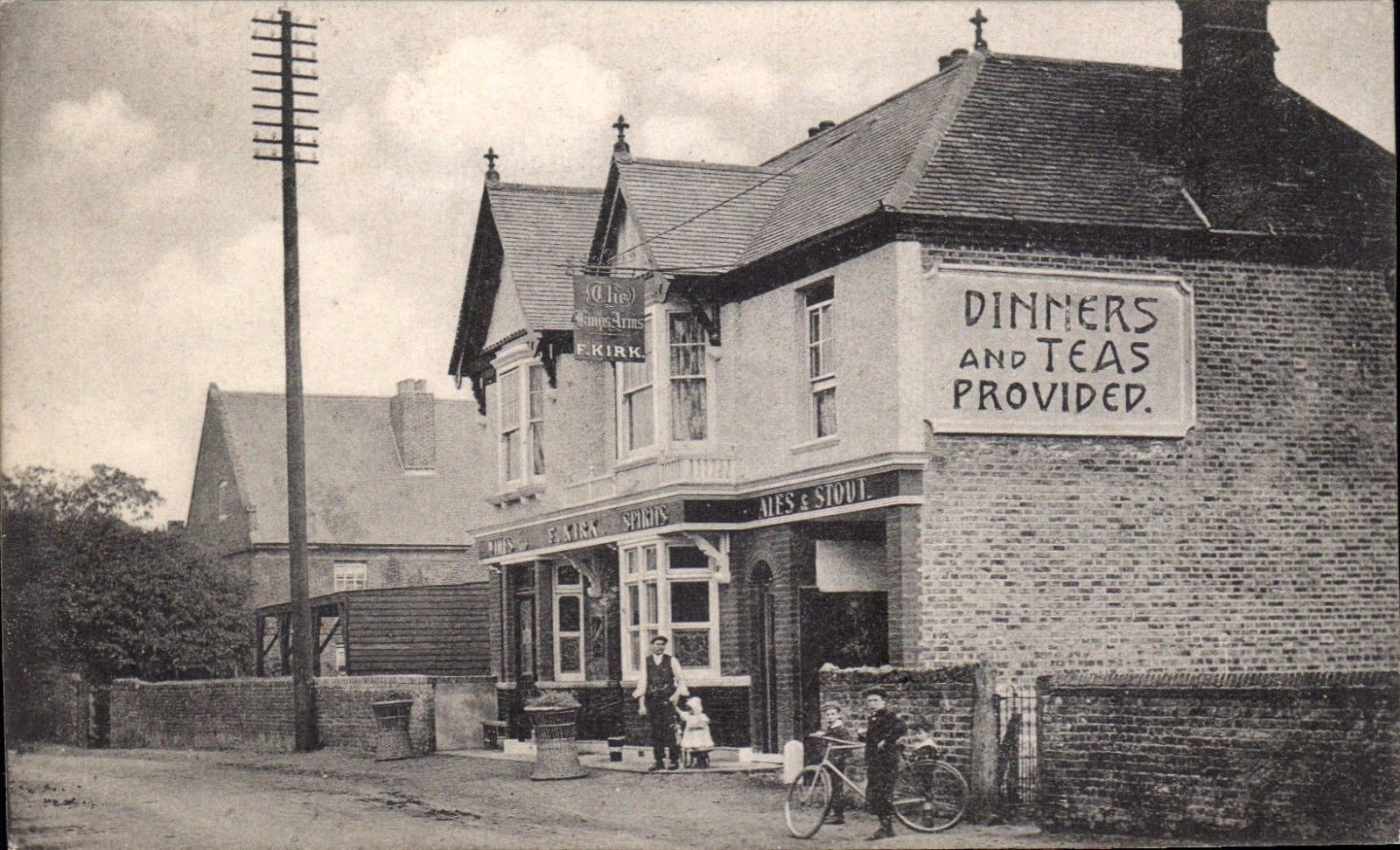

On 25 March 1946, Lord Winster took a party of M.P.s, Peers, the Press, and Foreign attaches, to Heath Row to show them the facilities. At luncheon he announced that the airport would, from now on, be called the “London Airport”, as it was considered that the name “Heathrow” would be “a difficult word for many foreigners”.[1] This decision was reversed in 1966. He said that when the airport is in full service it would be able to deal with 160 aircraft an hour in good weather. The first three runways would be completed by summer and when finished the airport would be one of the largest and best equipped in the world. He went on to say that London Airport is the greatest engineering enterprise ever undertaken, and although the buildings do not afford the entry into the United Kingdom that we should like, they will improve as time goes on.[2] Work had already started on acquiring land for extending the airport to the north of the Bath Road which would involve the destruction of Sipson and Harlington villages, although, he said, work on building these three new runways would not begin until after 1950 and no demolition will take place before then.[3] This expansion plan was dropped because of cost, but the spectre of airport expansion has hung over the residents ever since.

The airport was far from finished. After eighteen months of construction there was only one completed 3000 yard runway. At this time two million tons of earth had been excavated; 36,000 feet of ducting containing 60 miles of wire laid; 200 lorries, 40 excavators, 50 bulldozers used, as well as elaborate concreting equipment. More than 1000 men were housed and fed on the site.[4] However apart from the runways little else was ready.

One of the first casualties of this “modern” airport was the “Fido” installation at Heath Row. This was an experimental system for dispersing fog on the airfield.[5] It had cost £400,000 in total and was expensive to run and not very successful, so the Minister cancelled the project.[6] Fog became a big problem in the winter at that time of chronic air pollution and the low lying Heathrow land that was a fog pocket. Not only that, but with the land almost at sea-level the water-table was close to the surface, and was frequently water-logged.

The official opening of the airport to international aircraft took place on 31 May, when a BOAC Lancastrian arrived from Australia. It was two hours ahead of schedule, having completed the 12000 mile journey from Sydney in 63.25 hours.[7] Then a Pan-American Airways Constellation landed from New York. The flight took 14 hours with stops in Newfoundland and Shannon. The planes had landed in heavy rain and strong winds and the passengers had a dreary welcome. They had to walk on duck boards to reach the tented reception hall and customs house which were deep in mud from the recent rains.[8]

[1] Yorkshire Evening Post - Monday 25 March 1946

[2] Belfast News-Letter - Tuesday 06 April 1948

[3] Daily News (London) - Tuesday 26 March 1946

[4] Uxbridge & W. Drayton Gazette - Friday 04 January 1946

[5] Daily Express - Thursday 31 January 1946

[6] Dundee Evening Telegraph - Friday 20 December 1946

[7] Illustrated London News - Saturday 08 June 1946

[8] The Sphere - Saturday 29 June 1946

Only the Americans airlines were able to make the transatlantic flights because at that time Britain did not have planes capable of making the crossing with a payload of passengers. Lord Winster silenced the critics with assurances that the prospects were rosy and that although the Americans have their Constellations, Britain is developing its own long-range air transport.[1] He was referring to the development of jet aircraft.

While Lord Winster was defending Britain’s aircraft development he also had to deal with ground-level protests about the airport expansion plans. Local councils, from around the airport, sent a deputation to see Lord Winster on 11 April 1946, but they received no satisfactory outcome.[2] They had submitted a number of amendments to the new Civil Aviation Bill in the interests of the inhabitants of their areas, to mitigate the disturbance any new construction would cause. The Bill allowed for diversion of highways, construction of drainage and utilities, and demolition of houses for which the occupiers would only get the value at 1939 prices plus 30 per cent – not enough to find similar accommodation at the current house prices. The local residents, even without the airport’s expansion plans, were finding their voice. They also started to protest about aircraft noise.[3]

By September, with the increase in air traffic, there were worries about the inadequacy of radar at both Heathrow and Northolt airports, and the risk of accidents. The landing and take-off circuits at both airports, overlapped, and, as winter approached, concerns are being raised about the danger of poor visibility. The week before representatives from 37 countries, with 300 delegates, had met in London for a conference to discuss adopting international standards and common practice for radar technology. Britain’s radar pioneer, Sir Robert Watson Watt, estimated it will be two years before an international decision can be reached on standards for equipment, and a start made to install radar equipment on the ground at all international airports. At the conference the Government were keen to show the range of defensive radar equipment Britain had developed during the war, but delegates were astonished to learn that no civil airport in Britain had radar equipment. It was admitted that the Ministry of Supply and the R.A.F. could make this equipment available at the two London airports, but there had been no official explanation as to why this had not happened. It seems that although radar was developed as a means of defence, they were slow to recognise it had a new role in air safety.[4]

More complaints about the conditions at the London Airport were aired by The Sphere journalist in October. The Board of Trade were keen to promote tourism, but as the Sphere magazine pointed out any high-grade visitors will be put off by the conditions at London Airport. The great American composer and songwriter, Irving Berlin had just flown to Britain. His plane was due to land at 11pm, but didn’t arrive until 5am. A group of film executives, producers and music publishers were there to greet him. They had to wait six hours without even being able to get a cup of tea. Simple refreshments like hot drinks and a bun could only be obtained during normal hours. The airport had no drinks licence, and even some of the technical systems were primitive. The runway lights had to be switched on by a man and a bicycle going out to the runway to switch them on. If the wind changed and another runway was to be used then he had to repeat the time-consuming trip to change the lighting. Hangers had started to be erected, but they were not large enough for the transatlantic aircraft, and there was no hard standing to park aircraft, they had to be put on unused runways, and if there was a change in wind direction and that runway was needed suddenly, then there was a frantic scramble to tow the aircraft elsewhere. At this time nine major airlines and a few minor ones were using the airport. They did so knowing the airport facilities were primitive. By this time a few of the tents were being replaced by prefabricated single-storey buildings. Brick-built buildings were not expected to be erected for another two years. Critics believed the airport had opened before it was ready, especially as there was only provision for temporary maintenance of the aircraft. The aircraft had to be flown elsewhere for major repairs.[5]

The arrival of a B.O.A.C. Lancastrian plane from Sydney on 23 October 1946 marked the two-hundreth each-way trip on the longest and fasted air route in the world.[6] This achievement was over-shadowed by the fact that development at the airport had been halted by a week-long strike by the construction staff.[7] It was not a good start for the new Minister for Civil Aviation, Lord Nathan, but his troubles continued into the winter when fog was responsible for the cancellation of many flights.

January 1 1946 was a day of many firsts: the transfer of Heath Row airport from the Air Ministry to the Civil Aviation Ministry; the inaugural flight from the new civil airport for London; the resumption of civil flights in the UK post-war; and the day that B.O.A.C European Division took over commercial flights from 110 Wing of Transport Command.[8] It was a day of optimism. Air travel was seen as the future for Britain. It would make use of British engineering skills, boost jobs, and encourage tourism. The future looked bright.

[1] Daily News (London) - Thursday 10 January 1946

[2] Uxbridge & W. Drayton Gazette - Friday 21 June 1946

[3] Evening News (London) - Saturday 22 June 1946

[4] Daily News (London) - Monday 30 September 1946

[5] The Sphere - Saturday 19 October 1946

[6] Dundee Evening Telegraph - Wednesday 23 October 1946

[7] Gloucestershire Echo - Friday 25 October 1946

[8] Watson, Captain Dacre, BRITISH OVERSEAS AIRWAYS CORPORATION 1940 – 1950 AND ITS LEGACY, Journal of Aeronautical History, Paper 2013/03. https://www.aerosociety.com/media/4844/british-overseas-airways-corporation-1940-1950-and-its-legacy.pdf

For more historical stories of the area read:

“The Vanishing Village: A Legacy Lost to Heathrow’s Third Runway”

by Wendy Tibbitts

ISBN 978-1-7390822-2-22