"A fruitful source of Intemperance and Immorality”

The hard-working nineteenth century parishioners of Harmondsworth, had little time for pleasure. They worked six days a week, and on Sunday they were expected to worship at St Mary’s church or the Baptist Chapel. They had two annual public holidays on Christmas Day and Good Friday although for the day-work labourer this meant the loss of pay. However there was another non-working day that most people in Harmondsworth looked forward to, and that was Harmondsworth's annual fair held on 12 May. It was a time when people could dress in their best clothes and mingle on the centre of the village with their friends and neighbours for a day of enjoyment.

The day would dawn with many traders coming into the village and setting up stalls selling food and drink, trinkets, sweets, ribbons and beads. There would be some stalls for games where throwing or shooting at a target would result in a prize. There might also be simple fairground rides like swings and roundabouts. The fair was principally for pleasure, but it was probably also a hiring fair where employers who needed servants or labourers would mix with those looking for work. The farm workers would all wear their Sunday best and have a ticket or token in their hat, or carry an implement, that denoted their trade. Shepherds would have some sheep wool, and thatchers some straw in their caps. Horsemen would carry whips for, and labourers spades. The hat emblem would be replaced with ribbons if they were hired. The employer and the employee negotiated the wage, and if they agreed the bargain would be sealed with a token coin, usually a shilling, and this would soon be spent on the stalls around the green. It was a rare day off for the farm-workers and they made the most of it, but it often ended in rowdiness.

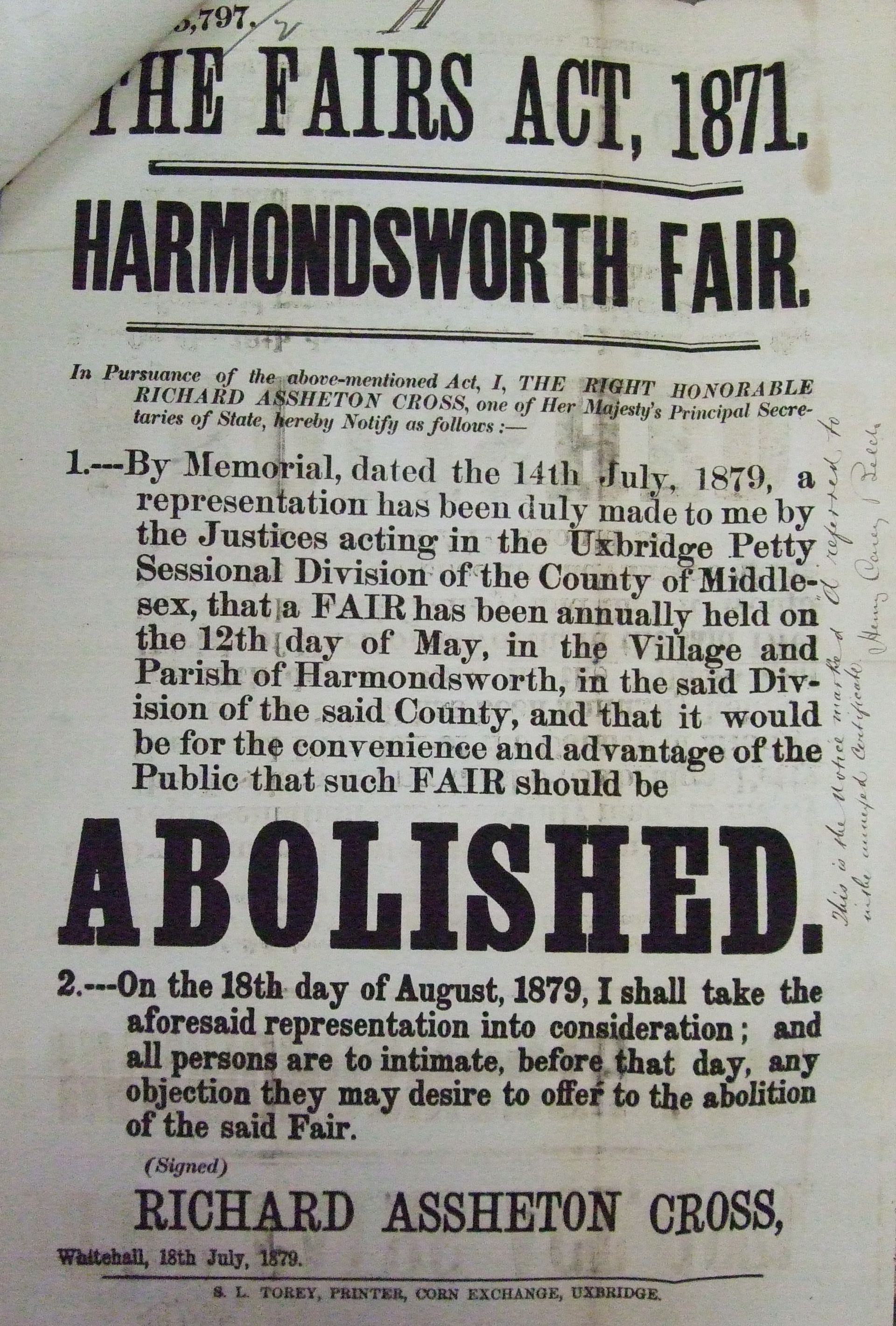

In 1871, The Fairs Act was passed into law by Queen Victoria on 25 May, which set out a framework under which citizens could apply to have Fairs abolished if they were: a) unnecessary; b) the cause of grievous immorality; c) injurious to the inhabitants of the towns in which such fairs were held. On the same day the widowed Queen also signed into law The Bank Holidays Act 1871. This would give the nation four more public holidays, i.e. Boxing Day; Easter Monday; the first Monday in May and the first Monday in August.

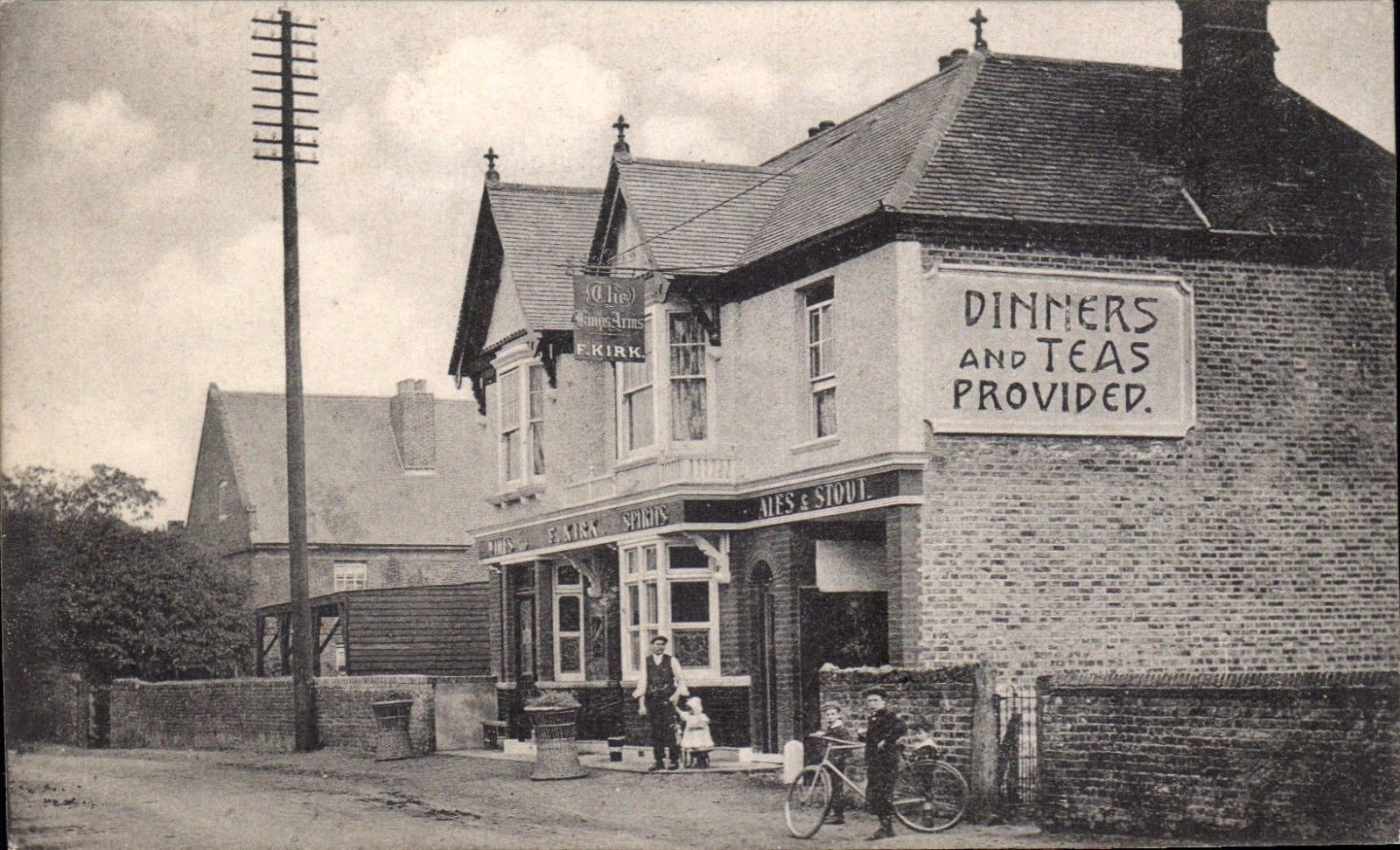

Now that the public had four extra days for pleasure, the Baptist farmers of Harmondsworth, and the churchgoers of St Mary’s felt that they did not have to put up with the dreaded nuisance of the annual fair which usually degenerated into a drunken, noisy event. On 19 May 1879, a petition was sent by to the Magistrates in Uxbridge asking them to apply to the Secretary of State, under the Fairs Act 1871, to have the fair abolished. Their reasons were that the fair had become “a nuisance to the neighbourhood, and a fruitful source of Intemperance and Immorality”. It was signed by J.C. Lewis, the vicar, his curate, Claud Brown, Charles A. Wild of The Grange, William G. Ashby, churchwarden, James Ladds at Cambridge House, Samuel Hunt, Guardian, Frederick Hunt, Chairman of the School Board, H.C. Belch, Surveyor of Highways, and W.H. Sternberg of St. Mary’s Cottage. Note that there were no representatives of Harmondsworth’s three pubs on the petition to whom the fair brought a welcome influx of people and their spending money.

On 15 July 1879 the clerk to the Magistrates forward the application to abolish the Fair on to the government and by 18th August a poster was displayed on the church door and three other places in the village proposing that the fair be abolished.[1] The announcement was also published in the Uxbridge and West Drayton Gazette. By 20th August the Secretary of State had signed the order and issued a certificate abolishing the Fair. Less than a year later the Secretary of State also approved the abolition of West Drayton’s annual Whit Monday Fair.[2]

These days we have plenty of leisure and plenty of choice on how we spend it. The nineteenth century Harmondsworth agricultural workers were less fortunate. They had little spare time and had no transport to travel further than they could walk. However, things were changing and soon, they could make the most of the four extra Bank Holidays by the use of a marvellous new invention called the bicycle.

[1] National Archives HO 45/9581/85797

[2] Uxbridge & W. Drayton Gazette - Saturday 17 April 1880

For more details of the history that will be lost if the Third Runway is built at Heathrow read my book "Longford: A Village in Limbo"

For a “Look Inside” option for this book go to