Tales from Longford -

The Pauper and the Pretty Girl

Figure 1: View of Harmondsworth from Summerhouse Lane across to the church tower and the Sunhouse.

Sarah Jarvis, a modest, pretty, sixteen-year-old girl, left the warmth of her married sister’s house in West Drayton to walk the two miles back to her home in Longford, Middlesex. It was mid-morning and she knew she would be needed at home soon to help her mother with the fourteen Jarvis children.

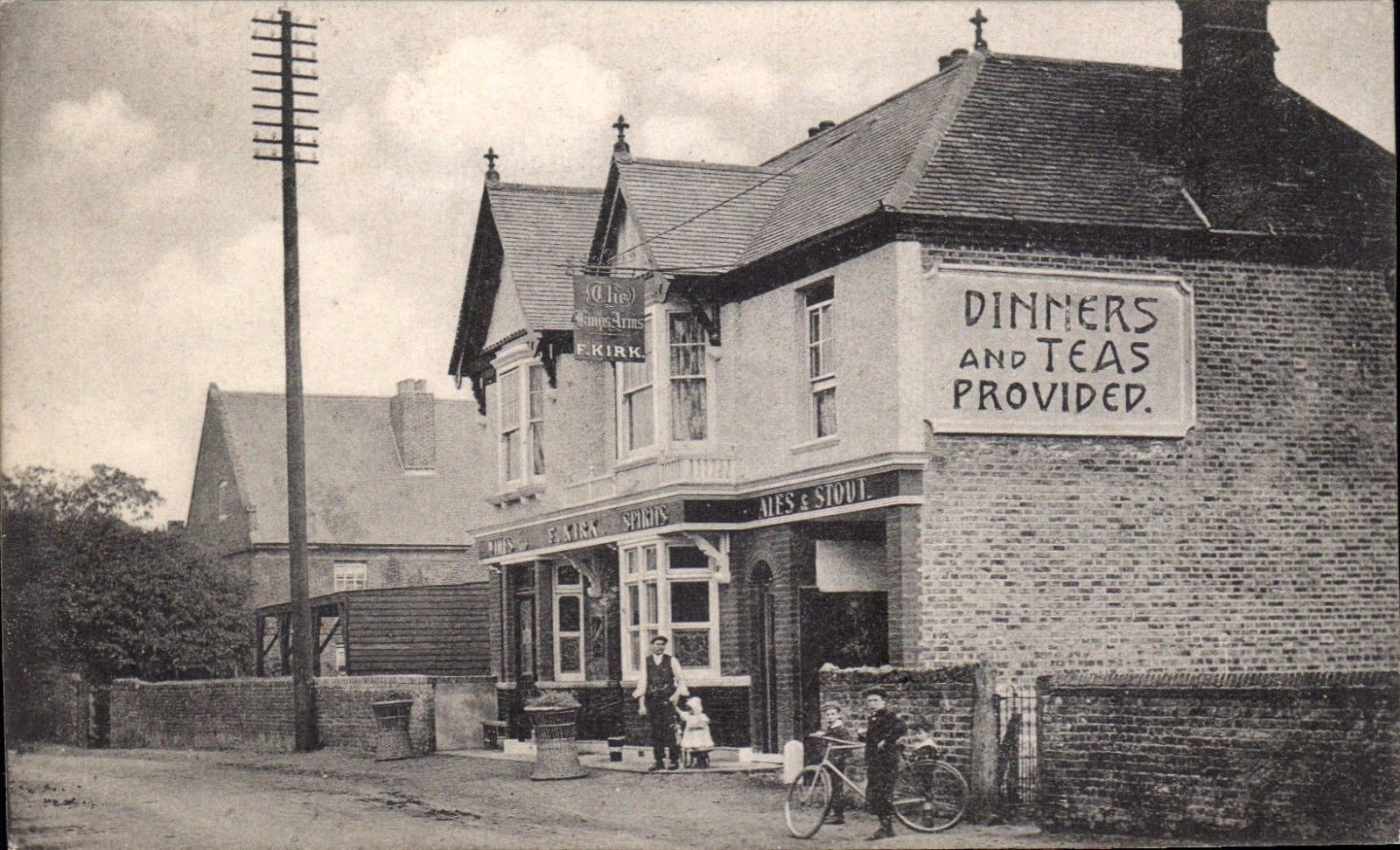

The end of March 1799 was colder than normal and she walked briskly to keep herself warm, wrapping her cloak around her and the bundle of items she carried for her father. As she walked along this familiar footpath, entering Harmondsworth village, between the Sun House and the churchyard of St Mary's, she crossed the High Street and walked down Summerhouse Lane and onto the field path that led to Longford.

She was walking close to the field-edge, treading carefully to avoid getting mud on her boots, when she was startled by a man who jumped out of a gap in the hedge and stood on the path close to her. She screamed as he grabbed her and was trying hard to fight him off, but he still managed to grab her bonnet, cap and cloak and ran off with them back through the gap in the hedge. Shocked and shivering she stood there in disbelief. It was cold without her cloak and she was frightened. She just wanted to get home as quickly as she could. She started hurrying towards Longford, but glancing behind saw the stranger had come back into the field and was running after her.

“Don’t hurt me. Here is my bundle you can have it if you leave me alone”.

She threw the bundle at him but he advanced towards her and knocked her to the ground, then he picked up the bundle and ran off.

Her father, James, was a labouring tenant of land in Longford. When she arrived home in a distressed state he immediately sent for the parish constable, William East, who went off in search of the offender. He caught up with him half-an-hour later on the other side of West Drayton heading towards Uxbridge, still carrying the bundle, which he intended to sell to buy food. The man, Thomas Green, a nineteen-year-old from Shropshire was arrested and tried at the Old Bailey less than a week later. Sarah, her father, and William East all gave evidence. The prisoner did not say anything in his defence and the Judge sentenced him to death.[1]

This sentence may seem harsh for just stealing a bundle of clothes, but the attack took place in a field close enough to a road to be classed as Highway Robbery, which carried a mandatory death sentence. A month later the sentence was respited to transportation for life. Green was transferred to a prison hulk to await his fate. Conditions on these old overcrowded decommissioned ships were deliberately harsh. On arrival the prisoner was given a metal plate, mug, blankets and basic clothing. The prisoners were shackled with leg irons and made to work for ten to twelve hours a day doing heavy manual work. The inadequate food, poor hygiene, and cramped conditions often caused disease to spread among the inmates.[2] At the turn of the nineteenth century, one in ten prisoners did not survive their punishment.[3]

After a year in the prison hulk, on 23 May 1800 Thomas Green was herded aboard the Royal Admiral with 301 other prisoners. They were shackled in leg irons and endured a long voyage in which 43 prisoners died before arriving in Sydney, Australia, on 20th November. Green was put to work making roads and after four years of good behaviour was given a conditional pardon and fifteen years later was a well-respected police constable in the Sydney suburb of Windsor. Inland areas around Sydney were the territory of the indigenous population, but in 1814 the New South Wales Governor, Lachlan Macquarie lifted restrictions on building on aboriginal lands. A road was built from Sydney, crossing the Blue Mountains, to Bathurst, the first inland settlement in Australia. The road, twelve foot wide and 100 miles long, was opened by the Governor in April 1815.[4] He travelled along the new highway with his wife and 50 officials, soldiers and servants. The party included Thomas Green.[5] However this was to be Thomas Green’s last journey. The road culminated in The Grand Depot, a small settlement of road-builders and soldiers. On 7 May the Governor raised the British Flag over the depot and a ceremonial volley of shots was fired by the soldiers. On the 12 May as the dignitaries started to return to Sydney, Thomas Green left his companions, to go with some ‘natives’ to their camp and was never seen again. It is not known whether he got lost in the bush or whether “he has fallen a victim to his own rashness in venturing among natives with whom we are so little acquainted”.[6] He was 35.

Sarah Jarvis, continued to help her Mother, Elizabeth, keep house and never married. She died aged 40, in Longford in 1824.

The extended Jarvis family remained in Longford until the twentieth century and were auctioneers and farmers. They farmed in various parts of the village including The Island, and later Bays Farm, where Bays Farm Court now stands.

Longford is threatened with demolition if the Heathrow expansion goes ahead.

My book, Longford: a village in Limbo, tells the story of the last three hundred years of Longford, Middlesex. For a “Look Inside” option for this book go to https://b2l.bz/WUf9dc

[1] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, 16 April 2020), 3 April 1799, trial of THOMAS GREEN (t17990403-26).

[2] https://www.royal-arsenal-history.com/prison-hulks.html

[3] https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/19th-century-prison-ships

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bathurst,_New_South_Wales

[5] https://convictrecords.com.au/convicts/green/thomas/100330

[6] Sydney Gazette Saturday 17th June 1815 p. 2