Death of an Eton Schoolboy

On Sunday, in February 1825, two schoolboys got into an argument after church which transcended into a fist fight, which had to be broken up by other pupils. The two schoolboys however demanded satisfaction and they agreed to meet for a bare-knuckle fight the following day. The schoolboys in question were the Hon. Anthony Francis Ashley Cooper, the fourth son of Lord Shaftesbury and Charles Alexander Wood, the son of Colonel Wood a politician, landowner and courtier. The boys were pupils at Eton College, the renowned boarding school for sons of the nobility.

Bare-knuckle fighting was illegal but it was a custom at Eton for differences to be settled by a “pugilistic contest”, at the end of which the victor shook hands with his adversary.[1] At four p.m. on 1st March 1825 a large group of scholars gathered to watch the contest. Mr Cooper had declared he would never give in, but by the eighth round he was beginning to tire. Some of his supporters gave him brandy to help him recover and the contest continued. Brandy was administered between every round and after nearly two hours, Cooper fell heavily and hit his head and fell unconscious. He was carried to his lodgings by his brother and put to bed. No one thought to call the doctor as he appeared to be sleeping, but four hours later when medical assistance arrived it was too late and the youth died.

The fight and its consequences were widely reported in The Times and other newspapers. The death of the son of such a high-ranking nobleman was discussed for some time and the sorrow was felt by many. Immediately after the death the Secretary of Lord Shaftesbury arrived at Eton to remove his two other sons from Eton. A Bill in Parliament had to be postponed when Lord Shaftesbury, Chairman of the Committees of the House of Lords, rushed off to Eton on hearing of the death of his son. Colonel Wood also arrived at Eton on hearing the news and “evinced much sorrow”. The whole college was in shock.

The Inquest.

The day after the death the inquest took place in the Christopher Inn in Eton. Mr Charsley the Coroner swore in the Jury and they all proceeded to walk to the deceased’s lodgings to view the corpse. They returned to the Inn where crowds of scholars were in the inn-yard and several Masters inside the Jury room. The Constable was asked to bring forward witnesses and he declared that he had been unable to find any. This was a surprising statement after the Times reported that the majority of scholars were present at the fight. The Constable declared that he had “inquired amongst the Collegians but they were not inclined to give him any information.” Mr Christopher Teasdale was presented to the Court. He said he was a student who knew both combatants and was present at the first fight but did not know what it was about. He heard they had agreed to fight the next day at 4pm. He was so reluctant to give any details that the Coroner had to admonish him. Another witness, Mr Carter, said he saw no foul blows struck and thought it was a fair fight. He said that after the 11th and subsequent rounds he did see brandy being given to Mr Cooper. The witness knew that Mr Wood had an appointment with a Master and heard him ask Cooper several times to postpone the fight, but Cooper and his second would not agree. After another round the deceased fell heavily and Wood said he must go. He was prepared to make up with his protagonist but by this time Cooper was unconscious. The witness thought Cooper had drunk about half a pint of brandy during the fight, although the Coroner declared that it was an exaggeration.

A surgeon was called as a witness. Mr O’Reilly said he visited the deceased on Monday night. He declared that the cause of death was a brain haemorrhage. The Coroner asked if this was caused by a blow or by a fall or by a natural cause. The doctor said it was caused by a violent fall, and if there had not been a four hour delay in calling for medical assistance there was a chance that the deceased might have survived.

In the Coroner’s summing up to the Jury he said “he had no hesitation in saying that he did not believe they entertained a feeling of malice towards each other which would make the offence murder”. However the killing of a person is an unlawful act and amounted to manslaughter. It was up to the Jury to decide if the deceased was unlawfully killed even though the fight appeared to be a fair trial of strength. After several hours the Jury returned a verdict of manslaughter against Mr Wood and Mr Cooper’s second, Alexander Wellesley Leith.

The funeral of the Hon. Anthony Francis Ashley Cooper took place at Eton on Sunday 6th March, a week after the initial altercation, and after the service his body was placed in a vault in the ante-chapel. A newspaper reported that the Provost would address the boys on the “impropriety of their recent conduct”, but this speech did not take place.[2] It suggests that the settling of disputes by fisticuffs was still regarded as acceptable by the school authorities. However the Times would not let the matter drop.

A week after the death the Times Leader wrote a scathing attack on Eton College. They reported that they had received a great many letters on the subject of the “melancholy event” at Eton. Normally, it said, they regard “crimes or calamities” at schools and colleges as accidental and they recognise that boys left to “their natural resources” will often end up fighting after a quarrel, and up to a point they advocate this. The fact that Cooper and Wood fought is accepted, but that the lads at Eton should be given brandy as a substitute for their natural stamina is to be condemned. The Leader went on to question the “astonishing ignorance” of the students at Eton who did not recognise the fact that if a boy is insensible and remains so for several hours he should receive medical attention. In other words The Times suggested that parents of scholars at Eton who hand guardianship of their children to the supposedly intelligent and experienced staff cannot be secure about their care.

The Headmaster of Eton College, Rev. Dr. Edward Craven Hawtrey, replied indignantly to the Times refuting their accusation of lack of care. He also reports that three gentlemen, returning from a hunt, came across the fight in the school playing fields about 50 minutes after it had commenced. They watched the fight for ten minutes and rode away after seeing nothing that warranted their interference.[3]

Many of the facts of the case were mis-reported in the newspapers and in the days that followed the papers had to print corrections. Colonel Wood reported that his son was 14 and not 17 as some had reported. Lord Shaftesbury took out an advertisement to say that only one of his sons took part in the fight. The other was confined to bed by a severe illness. Both parents were unhappy with the amount of publicity the matter was receiving.

The Trial.

Charles Alexander Wood was held in custody at the house of his tutor guarded by a Constable. The Earl of Shaftesbury declined to bring charges but the parties still had to be tried on the coroner’s warrant.

The Trial of Wood and Leith for manslaughter began at Aylesbury the following week. Both pleaded ‘Not Guilty’. Mr Wood was described by the Times as being of elegant appearance, aged about 14, but his “eyes were very much confused”.[4]

His coat sleeve was still torn from the fight. Mr Leith was aged about 19. No one appeared in Court to conduct the prosecution. The witness from the Coroner’s Court, Christopher Teasdale, was called three times, but did not appear. The Coroner was called who confirmed that he had given Teasdale, as well as two other witnesses, notice to attend, but none were present.

As there was no one to put the case for the prosecution the prisoners had to be acquitted and a Not Guilty verdict was given. An application to hear Mr Wood’s defence statement was refused and he returned with his father to London. Mr Leith also had a defence statement prepared had the trial proceeded. The Times printed his statement in full. Mr Leith disputed the amount of alcohol that was reported to have been administered to Mr Cooper during the fight. Leith said the deceased only sipped at the brandy between rounds and no more than one whole glass was consumed. He also said that it was not unusual for spirits to be given to contestants in fights at Eton, and that he was not the only supporter of Mr Cooper between rounds. He goes on to correct the report about the disparity in ages of the combatants and confirms they were of equal age. He concludes that he does not claim to be blameless, but thinks that the real cause of the fatality was inexperience.

After the trial the Times reported that Lord Shaftesbury had written to Colonel Wood, “couched in very friendly terms” in which he believed that no blame should be attached to young Wood in relation to the unfortunate affair and that he will continue to send his other sons to Eton.[5]

By publicly releasing this letter the Earl managed to end the newspaper’s attention on this whole affair and the public viewed the event as an unfortunate accident, although for those involved the memories of the fight might have been harder to eradicate.

Both boys were distraught over the death. It is not known whether this incident affected their later life. Alexander Wellesley Leith succeeded his father to the baronetcy in January 1842 and died three months later in Madeira at the age of 35.[6] He left a wife and son. In his short life he does not appear to have made any impact on society and his life is not chronicled in any biographical dictionary.

Charles Alexander Wood continued at Eton and then went on to study at Cambridge.

He became a Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioner responsible for superintending the sale and settlement of the waste lands of the Crown in the British Colonies “and the conveyance of emigrants thither”. He was the Treasurer of the Society of Ancient Britons and attended royal functions in that capacity. He was also deputy Chairman of the board of the Great Western Railway. He was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1874. He died in 1890.[7]

Conclusion.

The fact that both Colonel Thomas Wood and Major-General Sir George Leith, fathers of the accused, were present at the trial reflects on the parental concern of both men, but it is strange that there were no witnesses or prosecutors at the trial for such a serious charge.

For two weeks, until Lord Shaftesbury’s letter to Colonel Wood effectively put an end to the gossip and discussion, the case was reported daily in the newspapers. It was probably seen by the public as an indication that children of the rich and noble were no different in character to street urchins. It showed that an education makes no difference to a boy’s natural instinct to fight. The Times leader called fighting a form of duelling among boys, a natural activity which teaches courage and strength, and suggested that by venting their angry feelings it extinguished person hatred. This is seems to be the same attitude demonstrated by the Masters and staff at Eton who, at that time, appear to have shown a blind eye to the occasional fight among pupils.

[1] "Coroner's Inquest." Times [London, England] 3 Mar. 1825: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 16 Sept. 2016.

[2] "ETON, SUNDAY AFTERNOON.-The funeral of the Hon. F. A. Cooper, who was unfortunately killed on." Times [London, England] 7 Mar. 1825: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 16 Sept. 2016.

[3] "E. C. HAWTREY." "Eton School." Times [London, England] 9 Mar. 1825: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 16 Sept. 2016.

[4] "Aylesbury, Wednesday, March 9." Times [London, England] 10 Mar. 1825: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 16 Sept. 2016.

[5] "We understand that Lord Shaftesbury has written a letter to Colonel Wood, couched in very friendly terms, in." Times [London, England] 14 Mar. 1825: 2. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 16 Sept. 2016.

[6] "Deaths." Times [London, England] 9 May 1842: 9. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 24 Sept. 2016.

[7] “Obituary”Times, (London, England) 8 Apr. 1890: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Accessed 15 Sept 2016.

Read about the Eton Montem in my book: "Longford: A village in Limbo"

For a “Look Inside” option for this book go to https://b2l.bz/WUf9dc

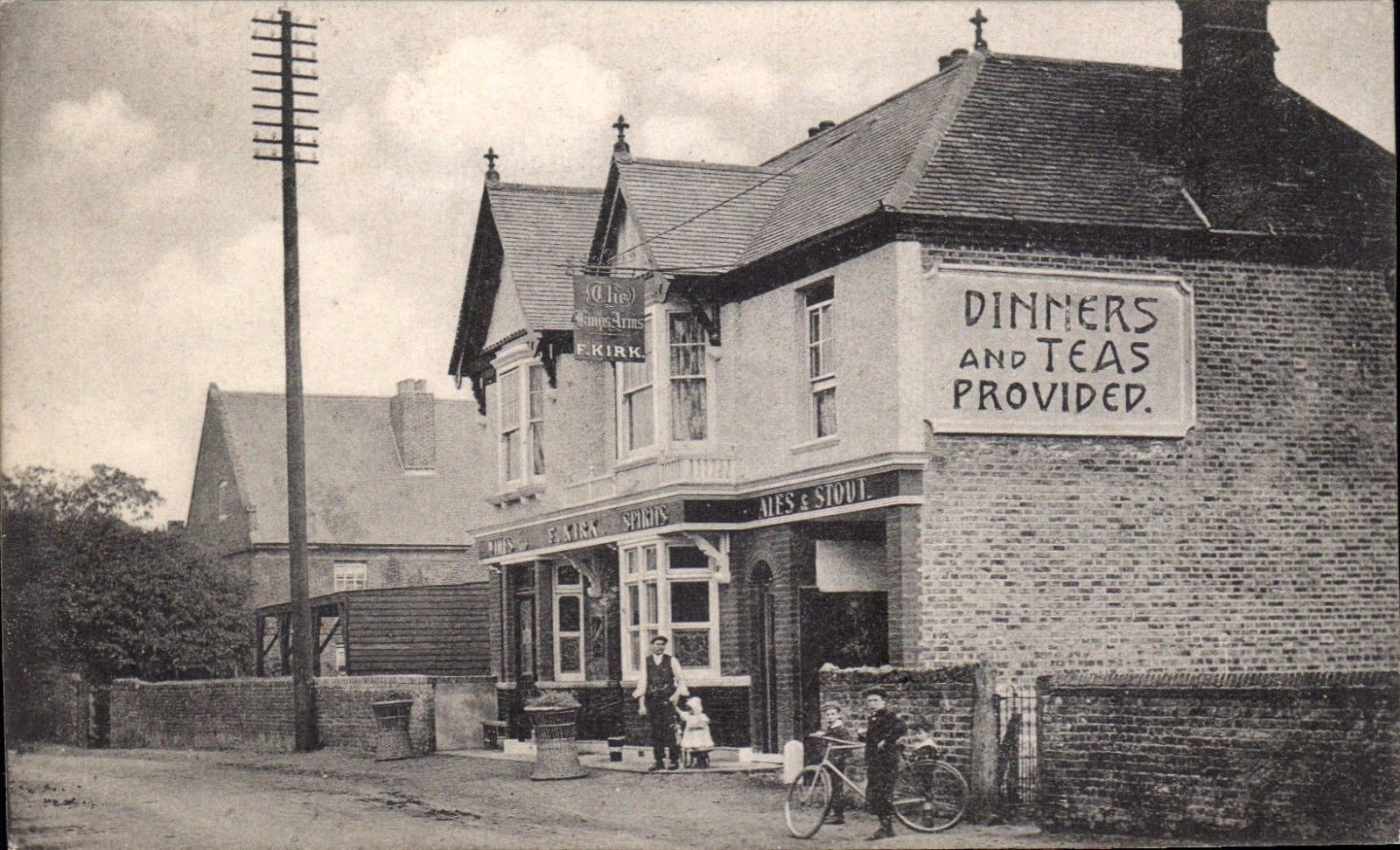

The villages around Heathrow have been blighted since 1946 as successive governments have procrastinated and made bad decisions about expanding the airport. These former rural agricultural villages have been fighting airport expansion for eighty years, meanwhile the Grade II listed buildings have deteriorated and the community are exhausted by years of protest.

The Kings Head later called The Peggy Bedford is a Grade II listed Elizabethan building in Longford, Middlesex, that was a major coaching inn on the Bath Road (A4) for centuries. Now blighted by the prospect of the whole village being demolished under the Heathrow expansion plans, it lies, empty and derelict and on the At Risk register.