Designated for destruction

When writing about history the biggest part of the project is research. Research is not just looking at documents in archives and reading academic books, but being out there walking the streets; talking to people.

I went on a research trip in August. I am researching the lost Middlesx community of Heathrow, as well as the soon to be lost villages of Longford, Harmondsworth and Sipson. If the London Airport Expansion plans go ahead hundreds of homes will be demolished in these places, which include eleven listed buildings in Longford, and twelve in Harmondsworth. Only Harmondsworth medieval Great Barn and its Norman church will survive the destruction, but who will want to visit them when they will be meters from the airport’s perimeter fence?

Right in the centre of Harmondsworth is Harmondsworth Hall which is now a guest house, and where I had booked a bed for the night. This grand-sounding building was built in the early 1700s, but still has elements of a fire-damaged Tudor building which was on this site. The central chimney and a fireplace are remnants of the former house. There are tales of ghosts in the garden, priest holes and secret tunnels. In the garden is the remains of an old cannon thought to have been put there by the wife of an Admiral after it had been captured off the Spanish Main. The Hall once had four acres of beautiful gardens in which were held church garden parties, tea dances, and barbecues (such a novelty in 1957 that they asked a member of the U.S.A.F. in nearby West Drayton to do the cooking). In 1910 this house was the first house in Harmondsworth to have its own electricity supply. It had a 7hp Hornsly Ackroid Oil engine and accumulators (batteries) which provided electric light for the house, but that was its only amenity. It still relied on a well underneath the scullery floor for a water supply and had no mains drainage. At this time the village had only just got piped gas to provide street-lighting.

The ownership of Harmondsworth Hall passed through many families and in 1957 belonged to Mr S.D. Brown and his family. Mr Brown worked in Paris but frequently flew home at weekends to the nearby London Airport which had become a civil airport in 1946. He applied for planning permission to build five detached houses in the four acre garden. The Middlesex County Council rejected the plan, but today there is a street of twentieth-century homes close to the Hall.

The house itself still has its original marble black and white chequered hall floor, wood panelling, and huge fireplaces. Externally the large sash windows are interspersed with window spaces bricked up to avoid paying a heavy tax bill during the eighteenth century when tax was levied on the number of windows in a building. It is beautifully kept, both inside and out, the rooms are sympathetically furnished and majestic, and the whole place has an air of grand antiquity. It was a pleasure and privilege to have had the experience of visiting this historic building before it is disappears forever.

Progress cannot be stopped, and humankind must grow to survive, but there is still a need to have reminders of the past in our midst. Without visible history to excite our curiosity we cannot measure progress and judge the effect of our actions in the future.

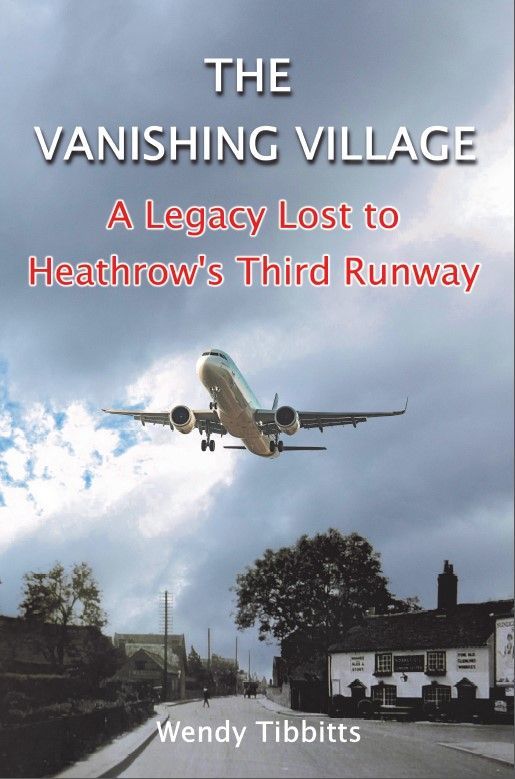

Read more about what will be lost in:

"Longford: A Village in Limbo" by Wendy Tibbitts.

For a “Look Inside” option for this book go to https://b2l.bz/WUf9dc

The villages around Heathrow have been blighted since 1946 as successive governments have procrastinated and made bad decisions about expanding the airport. These former rural agricultural villages have been fighting airport expansion for eighty years, meanwhile the Grade II listed buildings have deteriorated and the community are exhausted by years of protest.

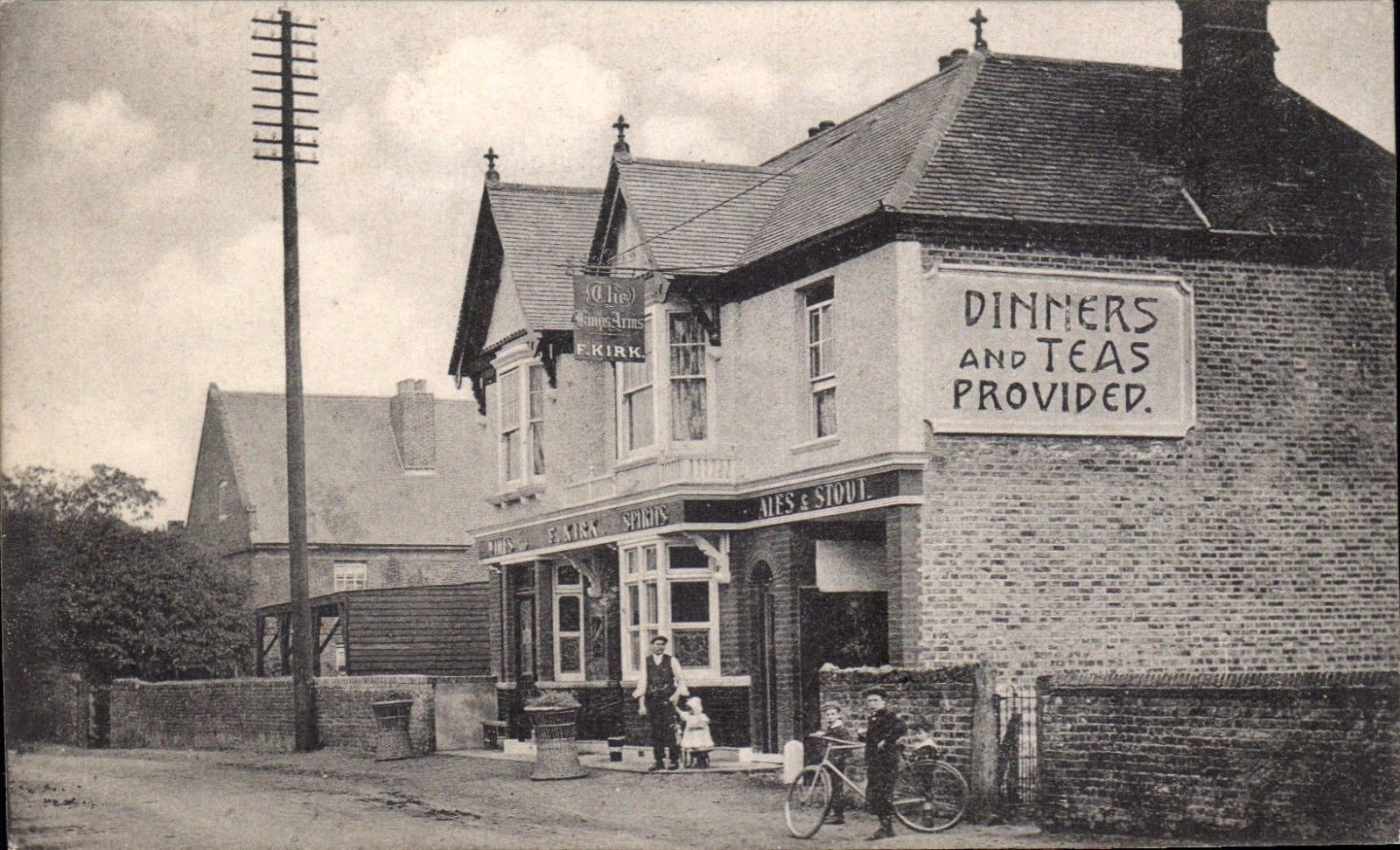

The Kings Head later called The Peggy Bedford is a Grade II listed Elizabethan building in Longford, Middlesex, that was a major coaching inn on the Bath Road (A4) for centuries. Now blighted by the prospect of the whole village being demolished under the Heathrow expansion plans, it lies, empty and derelict and on the At Risk register.